Improve Every

Tiny Thing by 1% and Here’s What Happens

No British

cyclist had ever won the Tour de France, but as the new General Manager and

Performance Director for Team Sky (Great Britain’s professional cycling team),

Brailsford was asked to change that.

His

approach was simple.

Brailsford believed in a concept that he referred to as the “aggregation of marginal gains.” He explained it as “the 1% margin for improvement in everything you do.” His belief was that if you improved every area related to cycling by just 1%, then those small gains would add up to remarkable improvement.

Brailsford believed in a concept that he referred to as the “aggregation of marginal gains.” He explained it as “the 1% margin for improvement in everything you do.” His belief was that if you improved every area related to cycling by just 1%, then those small gains would add up to remarkable improvement.

They

started by optimising the things you might expect: the nutrition of riders,

their weekly training program, the ergonomics of the bike seat, and the weight

of the tires.

But

Brailsford and his team didn’t stop there. They searched for 1 percent

improvements in tiny areas that were overlooked by almost everyone else:

discovering the pillow that offered the best sleep and taking it with them to

hotels, testing for the most effective type of massage gel, and teaching riders

the best way to wash their hands to avoid infection. They searched for 1%

improvements everywhere.

Brailsford

believed that if they could successfully execute this strategy, then Team Sky

would be in a position to win the Tour de France in five years time.

He was wrong. They won it in three years.

In 2012,

Team Sky rider Sir Bradley Wiggins became the first British cyclist to win the

Tour de France. That same year, Brailsford coached the British cycling team at

the 2012 Olympic Games and dominated the competition by winning 70 percent of

the gold medals available.

In 2013,

Team Sky repeated their feat by winning the Tour de France again, this time

with rider Chris Froome. Many have referred to the British cycling feats in the

Olympics and the Tour de France over the past 10 years as the most successful

run in modern cycling history.

And now for

the important question: what can we learn from Brailsford’s approach?

The

Aggregation of Marginal Gains

Almost

every habit that you have — good or bad — is the result of many small decisions

over time. And yet,

how easily we forget this when we want to make a change.

So often we

convince ourselves that change is only meaningful if there is some large,

visible outcome associated with it. Whether it is losing weight, building a

business, traveling the world or any other goal, we often put pressure on

ourselves to make some earth-shattering improvement that everyone will talk

about.

Meanwhile,

improving by just 1% isn’t notable (and sometimes it isn’t even noticeable).

But it can be just as meaningful, especially in the long run.

And from

what I can tell, this pattern works the same way in reverse. (An aggregation of

marginal losses, in other words.) If you find yourself stuck with bad habits or

poor results, it’s usually not because something happened overnight. It’s the

sum of many small choices — a 1% decline here and there — that eventually leads

to a problem.

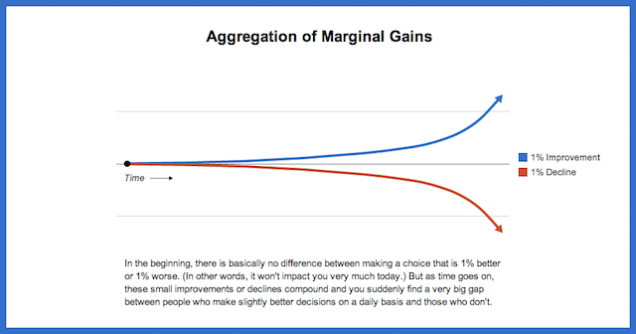

In the

beginning, there is basically no difference between making a choice that is 1%

better or 1% worse. (In other words, it won’t impact you very much today.) But

as time goes on, these small improvements or declines compound and you suddenly

find a very big gap between people who make slightly better decisions on a

daily basis and those who don’t.

This is why

small choices don’t make much of a difference at the time, but add up over the

long-term.

The Bottom

Line

Success is a few simple

disciplines, practiced every day; while failure is simply a few errors in

judgment, repeated every day.

—Jim Rohn

You

probably won’t find yourself in the Tour de France anytime soon, but the

concept of aggregating marginal gains can be useful all the same.

Most people

love to talk about success (and life in general) as an event. We talk about

losing 50 pounds or building a successful business or winning the Tour de

France as if they are events. But the truth is that most of the significant

things in life aren’t stand-alone events, but rather the sum of all the moments

when we chose to do things 1% better or 1%. Aggregating these marginal gains

makes a difference.

There is

power in small wins and slow gains.

Where are

the 1% improvements in your life?

No comments:

Post a Comment